______ __ __ ______ __ __ ______ ______ __ /\ ___\ /\ \/ / /\ __ \ /\ \ / / /\ __ \ /\__ _\ /\ \ \ \___ \ \ \ _'-. \ \ \/\ \ \ \ \/ / \ \ __ \ \/_/\ \/ \ \ \ \/\_____\ \ \_\ \_\ \ \_____\ \ \__/ \ \_\ \_\ \ \_\ \ \_\ \/_____/ \/_/\/_/ \/_____/ \/_/ \/_/\/_/ \/_/ \/_/

Disclaimer: This blog post is not meant to teach Vim, (that might come later) just to act as inspiration to start the learning journey.

If you’ve been convinced by this post and want to learn Vim, here are a few fantastic tutorials that helped me get started:

vimtutor, Vim’s built in tutorial, if Vim is installed on your system, just run vimtutor for an interactive tutorialAnyways… the post…

Vim stands for vi-improved. It builds off of the ideas of a previous text editor known as vi, which was created by Bill Joy (yeah that Bill Joy that worked on Unix, BSD, TCP/IP, Java, and NFS) back in 1976. Lots of programs back then were iterated on by others, since the source code was often available for modification. Vi is no exception.

One of the main groundbreaking ideas behind vi, and therefore Vim, is the idea of modal editing, where you switch between modes and keys do different things in each of those modes. This is in stark contrast to editors a lot of people are familiar with like Microsoft Word or the Google Docs editor, where every qwerty key simply inputs the corresponding character into the document. In Vim, this only happens when in ‘insert’ mode. When in the other modes, like ‘normal’ or ‘visual’ these same keys you use to input characters are instead used as keybinds for movement, editing, saving, quitting, etc. The most obvious advantage to this is that you can have significantly more keybinds than non-modal editors, since you simply have more keys to work with. Microsoft Word needs to use some hand-cramp-inducing combination of keys like Ctr-Shift-t for simple commands like cut or paste, when in Vim this can just be one key, right by the asdfjkl; homerow. This offers more specific keybinds that can significantly increase productivity, as well as reduce hand fatigue when typing for 8+ hours a day.

The other groundbreaking idea behind Vim (and vi) is command composition. We’ll dive into this in the next section, but essentially Vim has different types of commands like movement, editing, and repetition, which can be composed to increase their functionality. So you can apply any editing command to a movement command to apply it to that whole chunk of text (again, we’ll see examples shortly). This means that you can rapidly gain new functionality by learning just a few of the commands Vim has to offer; say you know 5 editing commands and 6 movement commands, since you can compose these by placing the editing command before the movement command, you now know 5 x 6 = 30 commands while only memorizing 5 + 6 = 11 keybinds! Having that same amount of editing power in MS Word would require learning all 30 keybinds.

Finally, Vim has a rich editing philosophy. A lot of the design decisions were made due to technical limitations at the time (no mouse, terminal screens only, slow computers that benefited from chaining sequential commands), but these decisions turn out to have modern day benefits as well (no back and forth between keyboard and mouse, easier on the hands and faster, composable commands allow for verbose, flexible expression of editing desires, commands offer easy automation for repetitive tasks, integrates with Unix Philosophy, etc), since good design is still good design, even 50 years later.

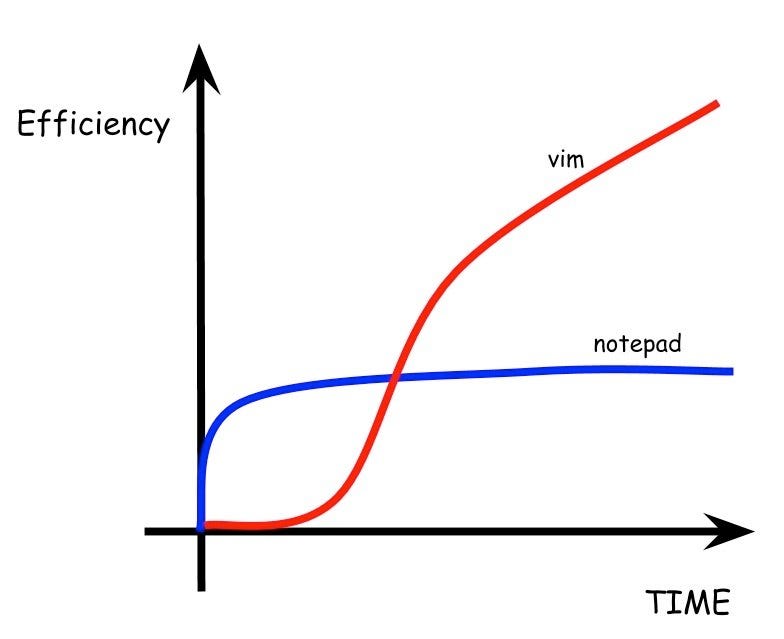

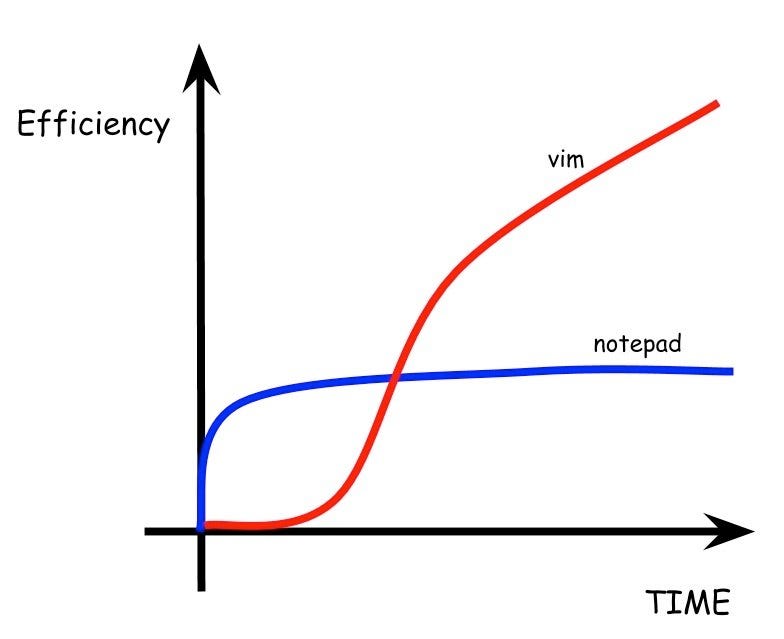

I think this photo sums it up well. Vim’s learning curve really is more like a learning wall, but once you’ve over that you will become exponentially faster as you learn more, and will soon overtake and far surpass editing capabilities in other text editors.

Also, Vim is free and open-source, like all good software is. No more VSCode sending telemetry data to Microsoft or Sublime prompting you to pay for a license.

Okay so, what are these different commands I keep talking about and why are they so powerful? Again, this isn’t a tutorial, but I’ll list the basics here so I can use them in examples.

i - enter insert modeEsc - return to normal moded - deletec - changey - copyp - pasteu - undoCtrl-r - redoh, j, k, l - move left, down, up, rightw - move to next work0 - move to beginning of line$ - move to end of line} - move to end of code block / paragraphgg - move to beginning of documentG - move to end of documentt<char> - move to next instance ofw - wordi" - inside quotesi{ - inside bracketsas - sentenceip - inside paragraphSo, the real power behind Vim is that these keybinds actually form a sort of editing language, with grammar and syntax like verbs, nouns, and adverbs. The general syntax for a “sentence” in Vim is <number><command><object or motion>. The numbers here act as an adverb, the commands act as a verb, and the objects and motions act as the noun to which the verb is applied.

As an example, we can run diw which runs the delete command on the inner word text object. So say the line we’re editing is as follows (with █ representing where the cursor is):

The quick brown fox ju█ps over the lazy dog.

If diw is run, the delete operation will run on the inner word object, and delete the entire word “jumps”, leaving just:

The quick brown fox █over the lazy dog.

This same delete command can be run on any motion or object. Here is an example of deleting the entire sentence with das (delete around sentence):

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. The quick b█own fox jumps over the lazy dog. The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.

Leaving just:

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. █he quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.

Or you could delete the entire paragraph with dap (delete around paragraph).

These ideas extend extremely well to source code. Consider the following example:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var greeting string = "He█lo, Reader"

fmt.Println(greeting)

}Here, say we wanted to change the value of the greeting variable. Of course, we could take a hand off the keyboard, move it over to the mouse, move the cursor to the desired spot on the screen, click and drag to select the desired text, and then finally hit backspace and start typing our new greeting… or, we could do it the Vim way, by simple hitting ci" (change inside double quotes) which will delete everything inside the quotes, and place us in insert mode ready to type.

var greeting string = "█"Or, we could change the entire function body by typing cip (change inside paragraph), leaving us in insert mode with the following:

func main {█}And finally, say we had a really annoying function call that we wanted to change out. Something like:

█MyReallyLong_Annoyingly_NamedFunction(SomeotherInnerFunction(greeting)).Print()And we want to change this entire function up until the .Print() call. No real combination of text objects or movements could delete this strangely worded function call. Is this finally a situation where the good ‘ol click and drag to select and delete wins over Vim? Of course not, we can use ct., which will Change To the next instance of a ”.”, leaving us in insert mode with:

█.Print()These commands can also take a numeric prefix, which represents the amount of time the command should run. A classic example is dd, which deletes the current line of text. By prefixing this with a number (say 5 5dd), Vim will delete the next 5 lines of text. Or 3cw will delete the next 3 words, and place you in insert mode to replace them. Essentially, this repetition allows you to work on many sections of text that don’t precisely correspond to a Vim keybind, which offers a lot of power.

In my opinion, these are really powerful movements, especially when editing source code. I find myself using ci" to change strings or } to jump between functions extremely often. And, like stated before, these command compositions work with any command and object/movement, so once you get the hang of targeting specific objects or movements, you can apply any of the commands we’ve learned so far to them, like delete, change, or copy.

Yes, there is a somewhat steep learning curve with Vim, and it’s not something I’d recommend to my parents who only type to search Google, but when your profession requires editing text for eight hours a day (developer editing source code, SysAdmin editing config files, DevOps engineer editing YAML, writer editing prose scripts or stories), the time spent learning the bread and butter of Vim will end up saving you a lot of time.

Furthermore, Vim commands like these let the computer do the hard work for you (like searching for the next parentheses), rather than making the human visually inspect where exactly to highlight and delete. This makes editing text, especially when these commands are ingrained in muscle memory, significantly faster, since the editor no longer needs to reach over to the mouse every time they want to make a simple change.

Vim, in my opinion, is best geared towards developers or operations people who edit source code or configuration files for most hours in a day. However, Vim can be as simple as, press i to enter insert mode, type your text, hit Esc to return to normal mode, and then :wq to save and quit. Noobs can use the mouse and arrow keys to navigate around while they learn the more efficient native Vim keybinds. Once a beginner has learned these few basic commands, they are likely just as fast in Vim as another text editor, with plenty of room to grow and speed up their editing. Vim is also extremely powerful for prose editing—I edit all my blog posts in Vim, using commands like (, {, cas, and cw to quickly jump around sentences, paragraphs, and reword sentences and change word choice.

Again, I don’t plan on making a Vim tutorial for the basics, I think other creators can do a much better job with that. Check out the videos linked at the top of this post if you want to dive into some more basic movement and editing commands of Vim. Later, I may post about more advanced Vim ideas like macros, buffers, plugins, or global commands. We’ve only scratched the very surface of Vim, but I hope this has been enough to convince you to give it a try. Live in Vim for a week or two, learn the basic commands and focus on efficient movement and editing, and I bet you’ll be hooked and it’ll feel sluggish to return to your old text editor.

The most fun part of Vim is learning, which I want to leave to you. I never thought I’d have fun and even look forward to editing text before I came across Vim. Some topics to look into after watching the basic tutorials linked above.

For those interested, here is my vimrc, which contains all the configuration, custom keybinds, plugins, and more that I use for my custom Vim editing experience.

last modified: (a683bf1)

the content for this site is CC-BY-NC-ND

the source code is MIT